Unraveling the Eternal: Egyptian Mummification

Throughout the lens of time, the practice of mummification in ancient Egypt stands as a testament to their profound reverence for life after death.

A detailed study of this extraordinary ritual illuminates not only the complex technical aspects involved but also the deep-seated religious beliefs that motivated the Egyptians to painstakingly preserve their dead.

Egyptian mummification dates back to 3500 BCE, then evolving, reaching its zenith during the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE) (Taylor, 2001).

Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and natural philosopher, detailed the process in his seminal work, “Natural History,” attesting to the meticulous nature of the process (Pliny the Elder, 77 AD).

Why did the Egyptians Mummify the Dead?

The primary aim of mummification was to preserve the body for the afterlife.

Central to their belief was the concept of ‘Ka,’ a spiritual double that, according to the Book of the Dead, needed the physical body as a dwelling place in the afterlife.

Without mummification, the body would decay, causing the ‘Ka’ to wander aimlessly and suffer (Allen, 2005).

This belief underscored the significance of the mummification process and the exceptional efforts the Egyptians invested in it.

The Mummification Process: A Step-by-Step

1. Purification and Organ Removal:

Once the individual passed away, the priests initiated the process, beginning with cleansing the body with palm wine, a substance believed to have purifying qualities (Herodotus, 440 BCE).

Next was the extraction of the organs, an essential step, considering that these were the first to decompose. Herodotus, the Greek historian, mentioned that a particular class of priests, known as the “paraschites,” were responsible for making an incision on the left side of the body to remove internal organs (Herodotus, 440 BCE).

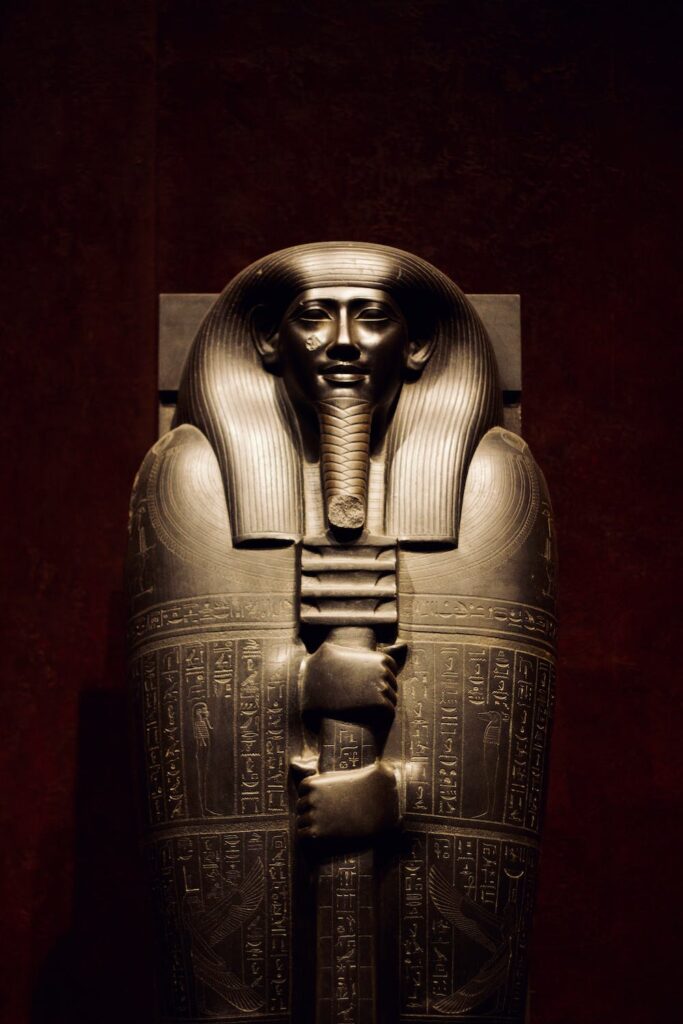

These organs – the liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines – were separately preserved in Canopic jars, each guarded by one of the four sons of Horus, the sky god. An exception to organ removal was the heart, deemed as the locus of intelligence and feeling, and thus left in the body for the individual to carry into the afterlife.

2. Dehydration:

The body was then treated with natron, a naturally occurring salt mixture, which helped desiccate the body, inhibiting bacterial growth. This process, typically lasting 40 days, was crucial in preventing the body from decaying (Ikram, 2003).

3. Stuffing and Wrapping:

After dehydration, the body was washed again and packed with linen or sand to regain a lifelike appearance. Following this, the body was wrapped in strips of linen, a process described vividly by Pliny the Elder. A resin-soaked linen cloth was applied to the body as an additional preservation measure (Pliny the Elder, 77 AD).

The process of wrapping was an intricate ritual, with amulets and prayers incorporated into the folds to protect the deceased in the afterlife. Finally, a death mask, often bearing the likeness of the deceased, was placed over the head and shoulders (Taylor, 2001).

The Social and Economic Dimensions of Mummification

The mummification process, as complex as it was, varied significantly based on the social and economic status of the individual. While the wealthy could afford the “first” and most elaborate method described by Herodotus, which involved brain extraction and organ preservation in Canopic jars, not everyone could afford such a detailed procedure (Herodotus, 440 BCE). For the less affluent, less expensive methods were available, but these involved fewer preservation steps, resulting in less well-preserved mummies.

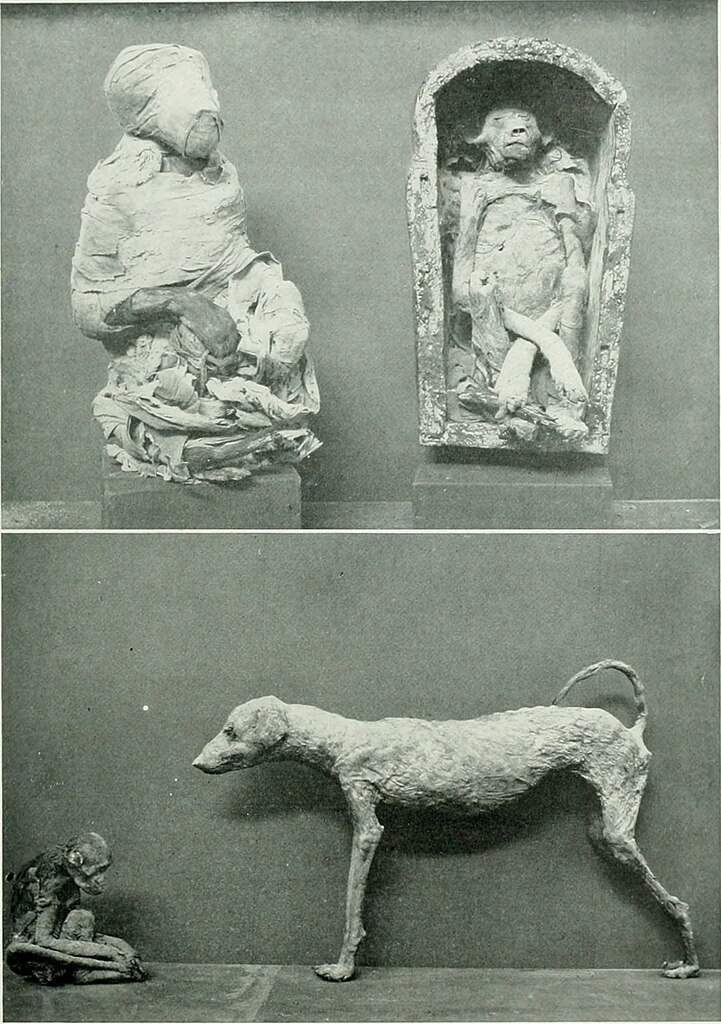

The economics of mummification even extended to the animal kingdom. Millions of animal mummies, from cats and dogs to crocodiles and ibises, have been found in Egypt, often offered as votive offerings to the gods. The scale of this practice indicates an entire industry built around animal mummification (Ikram, 2005).

A Testament to a Timeless Belief

The elaborate process of mummification, facilitated by a sophisticated understanding of the human body and preservation techniques, underscores the ancient Egyptians’ profound belief in the afterlife.

From Herodotus’ accounts to Pliny the Elder’s detailed descriptions, the complex, meticulous nature of this ritual is indeed a testament to a timeless belief.

References:

Allen, J. P. (2005). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. (Find Here)

Herodotus. (440 BCE). The Histories. (Find Here)

Ikram, S. (2003). Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt. Longman. (Find Here)

Pliny the Elder. (77 AD). Natural History. (Find Here)

Taylor, J. H. (2001). Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. University of Chicago Press. (Find Here)

Check this out

“Fun Fact: Did you know that not all mummies are ancient? The last known Egyptian-style mummification was performed on a high-ranking monk of the Coptic Church in Egypt in 1942. This underlines the lasting influence of these ancient practices, persisting in some form even into the modern era.”

If our journey into the art of mummification captivated you, don’t miss the opportunity to delve into another intriguing topic. Discover the mystery behind the abundance of pyramids in our next article. Just click the button below to continue your exploration of ancient Egyptian wonders.