An Exploration of Archaeological Frauds

Archaeology, the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains, has undoubtedly deepened our understanding of the world.

It uncovers the secrets of ancient civilizations, enlightening us about the lives, cultures, and practices of our ancestors.

However, like many scientific disciplines, archaeology is not immune to deception.

Frauds and hoaxes have cropped up throughout its history, misleading researchers and the public, while also casting doubt on genuine discoveries.

This article delves into some of the most infamous archaeological frauds, such as the Piltdown Man, Cardiff Giant, and Fawcett’s Deadly Idol, and explores their impact on the field of archaeology.

The Piltdown Man

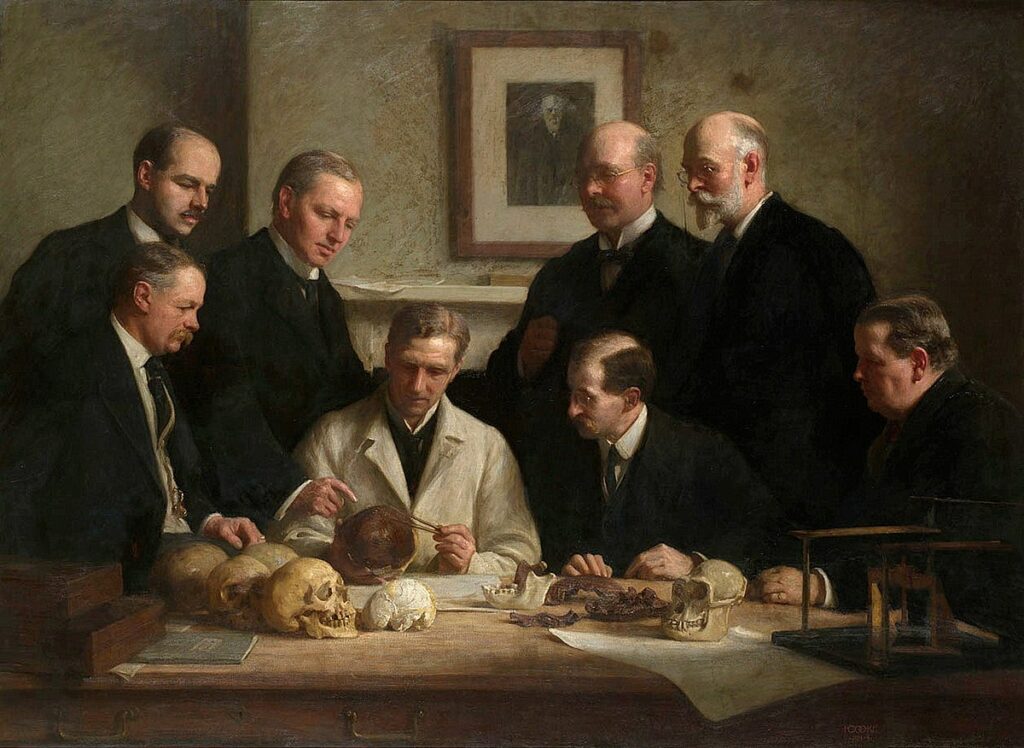

One of the most notorious frauds in the history of paleoanthropology is the Piltdown Man, a supposed “missing link” in human evolution. Unearthed in 1912 by Charles Dawson, an amateur archaeologist, the Piltdown Man consisted of fragments of a skull and jawbone found in Piltdown, East Sussex, England. These remains were believed to be those of an early human ancestor that lived about 500,000 years ago.

The discovery was initially hailed as a significant find, as it appeared to fit perfectly within the evolutionary framework of the time. The skull suggested a large brain capacity akin to that of Homo sapiens, while the ape-like jaw indicated a primitive diet. It was seen as the ideal ‘transitional’ specimen, filling the gap between ape and human.

However, over 40 years later, in 1953, advanced dating techniques and further examinations revealed the Piltdown Man to be an elaborate hoax. The skull was identified as being only a few thousand years old, with the jawbone belonging to an orangutan. The teeth had been artificially worn down, and the bones stained to give an appearance of antiquity.

The Piltdown Man hoax disrupted the trajectory of paleoanthropological research, leading scientists down a decades-long rabbit hole that detracted from the study of actual early human fossils. It also highlighted the danger of confirmation bias in scientific investigation, prompting a re-evaluation of methods used to authenticate archaeological finds.

The Cardiff Giant

The Cardiff Giant, a 10-foot-tall supposed “petrified man,” unearthed in 1869 in Cardiff, New York, represents another infamous hoax that initially captivated the public’s imagination. George Hull, an atheist and cigar manufacturer, orchestrated the deception as an elaborate prank to mock those who took Bible scriptures about giants literally.

The colossal figure, carved from a block of gypsum, was claimed to be a fossilized human from ancient times, attracting widespread interest and turning into a lucrative exhibition. However, Hull’s ruse was soon revealed, especially after he confessed to the hoax following a financial dispute with his business partner.

While the Cardiff Giant was more of a spectacle than a serious archaeological find, it served to highlight the gullibility of the public and the need for rigorous scientific scrutiny in the field of archaeology. It also underscored the fact that fraudulent artifacts could be created for reasons beyond scientific deception, including ideological disputes and financial gain.

Fawcett’s Deadly Idol

Adding another intriguing layer to the world of archaeological hoaxes is the tale of Lieutenant Colonel Percy Fawcett’s lost city of Z and his infamous Deadly Idol.

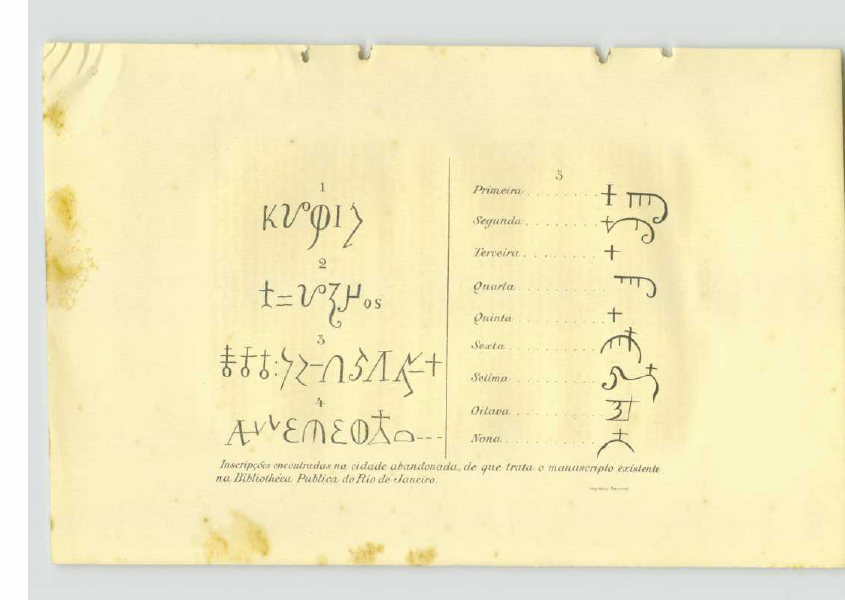

Percy Fawcett, a British explorer, made several trips to South America in the early 20th century in search of a legendary lost city he referred to as ‘Z’. His journeys were based on a document he discovered in the National Library of Rio de Janeiro, known as Manuscript 512. This document, supposedly written by a Portuguese explorer in the 1750s, described a city full of gold and advanced civilization in the Amazon’s heartland. Fawcett formulated a theory that the city was the remnants of an ancient, sophisticated civilization.

One of the key elements in Fawcett’s tale was a statue he referred to as the ‘Deadly Idol.’ This artifact was said to be made of a high-grade alloy, featuring a strange set of hieroglyphics. Fawcett believed that anyone who touched the Idol would die instantly, thus giving it its ominous name. While Fawcett himself never claimed to have found this artifact, he alleged its existence based on the accounts of local tribespeople and other explorers.

Despite several attempts, Fawcett never managed to find the city of Z. His final expedition in 1925, accompanied by his eldest son Jack and Jack’s friend Raleigh Rimell, ended with their mysterious disappearance. Their fate remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of exploration history.

The story of Fawcett’s Deadly Idol and the lost city of Z has since been largely debunked by modern archaeologists. There’s little credible evidence to support the existence of either the Idol or the city. Many consider Fawcett’s tale a product of the period’s fervor for exploration and discovery, fueled by the public’s fascination with tales of lost civilizations.

The impact of Fawcett’s Deadly Idol story, while not a hoax perpetrated by Fawcett himself, illustrates the power of narrative and speculation in shaping public perception. It demonstrates how the allure of the unknown can sometimes overshadow the rigorous analytical processes that should underpin archaeological research. Furthermore, it also serves as a reminder of the dangers faced by explorers in their quest for discovery and the human cost that can sometimes accompany such endeavors.

Impact on Archaeology

Hoaxes like the Piltdown Man, Cardiff Giant, and Fawcett’s Deadly Idol have had a profound impact on archaeology and related fields. They underline the importance of applying rigorous scientific methodologies, ensuring the veracity of findings before their acceptance into the scientific canon. These incidents have led to the development of more advanced techniques for dating and authentication, along with an increased focus on cross-verification among researchers.

Furthermore, these hoaxes demonstrate the potential for fraudulent finds to mislead not just scientists but the public as well. They emphasize the critical role of public education in promoting an accurate understanding of human history and the processes through which it is discovered and interpreted.

Finally, these deceptive incidents have also had a silver lining. While they have certainly caused considerable harm, they have also served as catalysts for change, sparking discussions about scientific integrity, methodology, and public understanding of archaeology. In this way, they have inadvertently contributed to the evolution and strengthening of the field.

Archaeological frauds and hoaxes, despite their destructive impact, offer crucial lessons.

They underline the importance of skepticism, scrutiny, and methodological rigor in scientific pursuit.

As we continue to unearth our past, these episodes of deception serve as reminders of the pitfalls to avoid, thereby fostering an environment of honesty, integrity, and intellectual rigor that is so vital to the discipline of archaeology.

Check this out

“Fun Fact: Did you know that the Cardiff Giant hoax was so successful that it inspired a famous phrase? When P.T. Barnum, the renowned showman, created a replica of the Cardiff Giant after failing to acquire the original, he displayed it as the real thing. When his fraud was exposed, he reportedly responded, “The public appears to be getting fooled all the time. I don’t see why a man can’t get rich by fooling the public.” This comment is often simplified as the saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute” – a phrase commonly (though incorrectly) attributed to Barnum himself!”

If you enjoyed our deep-dive into the world of archaeological frauds and hoaxes, we invite you to delve into our collection of articles that shed light on authentic artifacts. You can access these fascinating reads by clicking on the link provided below.